By: Lizzy Ritchie, Editor-In-Chief

The Fifth Amendment Takings Clause of the United States Constitution prohibits the government from taking private property for public use, without paying the property owner just compensation.[1] So long as the government provides just compensation, it is authorized to exercise its eminent domain power pursuant to the public health, safety, morals, or welfare.[2]

The Supreme Court of the United States has articulated several regulatory takings tests to determine when takings that demand just compensation occur.[3] Unlike ordinary regulatory takings, which are subject to the three-part Penn Central balancing test,[4] the Court held that land exactions[5] are subject to heightened scrutiny under the Nollan/Dolan two-part “rough proportionality” test to prevent the government from attaching unconstitutional conditions to land-use permits.[6] To pass constitutional muster, land exactions must adhere to the requirements of the Nollan/Dolan test: (1) when the government demands an exaction, it must have an “essential nexus” with a police power objective;[7] and (2) the government demand must be “roughly proportional” to the proposed project.[8] In Koontz v. St. Johns River Water Management District, the Court extended the Nollan/Dolan framework to monetary exactions.[9] Evaluating Koontz and the differing perspectives on its outcome reveal the public policy concerns related to subjecting monetary exactions to heightened scrutiny.

Koontz v. St. Johns River Water Management District

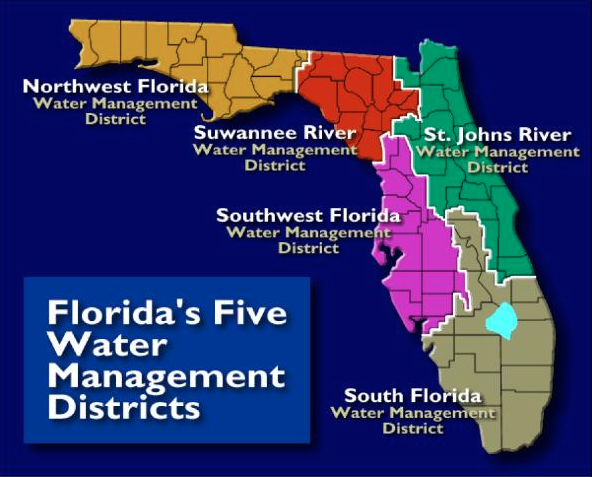

In Koontz, a Florida resident wanted to develop a portion of his land, but much of his land was in an area classified as wetlands.[10] Meanwhile, the Florida legislature enacted the Water Resources Act, which divided the state into Water Management Districts responsible for regulating construction that would impact “waters in the state,” and required landowners to obtain construction permits to ensure that development would not harm the district’s water resources.[11]

The Florida legislature then enacted the Henderson Wetlands Protection Act, which made it illegal to “dredge or fill in, on, or over the surface waters” without a Wetlands Resource Management Permit.[12] St. Johns River Water Management District (“St. Johns”) required permit applicants seeking to construct on wetlands to offset environmental damage by creating, enhancing, or preserving wetlands elsewhere.[13] Koontz wanted to develop a portion of his property, and sought a permit to dredge and fill several acres of his parcel.[14] Although Koontz offered a conservation easement on another part of his land, St. Johns found this proposal insufficient and demanded that Koontz develop less of his land and hire a contractor to improve wetlands several miles away.[15] This was a requirement to spend money. Koontz rejected St. Johns’ counteroffer, and argued that St. Johns’ demands failed the Nollan/Dolan “rough proportionality” test.[16]

When the case reached the Supreme Court, Justice Alito held for the majority that this was a taking in violation of the Fifth Amendment, and that the Nollan/Dolan framework must apply to monetary exactions.[17] Justice Alito found that monetary exactions were the functional equivalent of other land exactions, and to hold otherwise would allow local governments to “evade the takings clause by charging a fee” instead of “demanding a property right.”[18] Further, the Court reasoned that the unconstitutional conditions doctrine is violated when the government conditions permit-approval on a monetary payment that “burdens” a property owner’s use of his property (e.g., developing a portion of his property), which occurred in this case.[19]

However, Justice Kagan wrote a compelling dissent, finding that requiring Koontz to fund repairs of public wetlands was not a taking, because it did not affect a “specific and identified property right,” but instead “simply impose[d] an obligation to perform an act”—i.e., to pay money. She would have held that the constitutional right to just compensation is only violated when the government conditions a land use permit on an actual transfer of a real property interest.[20] Because government demands for monetary payments during the land use permitting process arise from that process rather than a specific property interest, Justice Kagan found that the Nollan/Dolan “rough proportionality” test is not implicated and does not apply to monetary exactions.[21]

Differing Perspectives on Monetary Exactions and Koontz

Differing perspectives on monetary exactions shed light on the importance of the Koontz decision. From the property owner’s perspective, the Supreme Court’s decision in Koontz was a victory because it required any condition attached to a land use permit to pass heightened scrutiny under Nollan and Dolan.[22] Koontz limited the government’s ability to use permitting processes and other land use restrictions as tools to force property owners to perform public services.[23] Without the Court’s Koontz decision, the government could practically wipe out property owners’ rights by refusing to allow them to develop their land, unless they meet the state’s demands.[24]

From the local community’s perspective, there might not be sufficient infrastructure, such as affordable housing to offset the economic forces that push low-income residents out of their neighborhoods, in the wake of Koontz.[25] In turn, the Koontz holding raises residents’ concerns about development project impacts on their communities.

From the local government’s perspective, Koontz restricts municipalities’ abilities to fund infrastructural maintenance and improvements. Revenues that local governments collected from monetary exactions financed the necessary improvements that new development created.[26] Local governments have tight budgets and must be able to fund public improvements.[27] Therefore, property owners and developers should share the publicly generated costs to help pay for bridges, transit systems, parks, affordable housing, and other improvements.[28]

Although Justice Alito and Justice Kagan raise plausible arguments in their Koontz opinions, a review of differing perspectives on Koontz reveals concerns associated with subjecting monetary exactions to heightened scrutiny. While property owners are relieved that the government cannot force them to essentially pay for public services in order to obtain development permit approval, local governments must be able to finance infrastructural maintenance and improvements to offset development impacts. Without the local government’s ability to finance infrastructure, local communities suffer. Perhaps monetary exactions should be subject to the three-part Penn Central balancing test like ordinary regulatory takings, but only time will reveal whether the Supreme Court’s decision to subject monetary exactions to heightened scrutiny was correct.

[1]U.S. Const. amend. V.

[2]Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U.S. 365 (1926).

[3]See, e.g., Lucas v. S.C. Coastal Comm’n, 505 U.S. 1003 (1992); Loretto v. Teleprompter Manhattan CATV Corp., 458 U.S. 419 (1982);Penn. Cent. Transp. Co. v. N.Y.C., 438 U.S. 104 (1978).

[4]Penn. Cent. Transp. Co. v. N.Y.C., 438 U.S. 104, 124 (1978) (holding that in respect to whether a regulatory taking occurred, there are three factors to consider: the economic impact of the regulation on the claimant, interference with the property owner’s investment-backed expectations, and the character of the governmental action).

[5]Land exactions are government-imposed conditions that demand a property owner to dedicate a portion of his or her land to offset the impacts of the property owner’s development, in exchange for development permit approval.

[6]Koontz v. St. Johns River Water Mgmt. Dist., 570 U.S. 595, 622 (2013) (Kagan, J., dissenting).

[7]Nollan v. Cal. Coastal Comm’n, 483 U.S. at 837. Monetary exactions are government demands for monetary payment, in exchange for development permit approval, to mitigate or offset the impacts of the applicant’s development project.

[8]Dolan v. City of Trigard, 512 U.S. at 391, 396.

[9]Koontz, 570 U.S. at 601 (majority opinion).

[10]Id. at 599-600.

[11]Id. at 599-600.

[12]Id. at 600-01.

[13]Id. at 601.

[14]Id. at 600-601.

[15]Id. at 601-02.

[16]Id. at 602.

[17]Id. at 612, 619.

[18]Id. at 612.

[19]Id. at 606.

[20]See id. at 619.

[21]Id. at 626.

[22]Aaron McKean, Local Government Legislation: Community Benefits, Land Banks, and Politically Engaged Community Economic Development, 24 J. of Affordable Housing133 (2015).

[23]Ilya Somin, Two Steps Forward for the “Poor Relation” of Constitutional Law: Koontz, Arkansas Game & Fish, and the Future of the Takings Clause216(Ilya Shapiro ed., 2013).

[24]Id. at 217.

[25]McKean, supranote 107, at161-62.

[26]Lourdes Germán & Allyison E. Bernstein, Land Value Capture: Tools to Finance Our Urban Future, Lincoln Inst. of Land and Pol’y,https://www.lincolninst.edu/sites/default/files/pubfiles/land-value-capture-policy-brief.pdf (2018).

[27]Id.

[28]Id.