Written By Nicole Daudelin L’27

The United States criminal justice system has long struggled or entirely failed to address issues of domestic violence.[2] For years, domestic violence was known about and ignored by government and law enforcement officials because it was considered to be an issue that should be handled privately by those involved.[3] However, all levels of governments are finally beginning to treat domestic violence more seriously and are prosecuting perpetrators, leading to increased focus on the victims of these crimes.[4] Adult women are by far the most likely intended victims of domestic violence but domestic violence often has farther reaching impacts than the physical and psychological injury faced by the intended victim.[5] Children are often unintended victims of domestic violence, with estimates of between three and ten million children being exposed to domestic violence in the United States annually.[6]

Children who witness domestic violence in their household are typically impacted in similar ways to children who are the direct victims of abuse, though the impacts might be less severe.[7] Importantly, witnessing inter-parental violence can have more noticeable impacts on children’s developmental problems compared to witnessing other types of violence.[8] Generally, children who witness inter-parental abuse may have more mental health issues, behavioral issues, emotional issues, learning difficulties, and are often more likely to develop negative coping skills or violent tendencies compared to those who have not witnessed domestic violence.[9]

Research shows that children who had previously witnessed domestic violence were more likely to interpret inter-parental situations as threatening and were also more likely to react with fear to normal parental interactions compared to children who had not witnessed domestic violence.[10] In addition to fear, children who witness domestic violence are more likely to show increased levels of aggression as they grow older.[11] Though this aggression can manifest itself in many ways, such as verbally, nonverbally, passively, and physically, studies show that children who witness domestic violence are more likely to become perpetrators of domestic violence later in life.[12]

Mental health impacts on children who witness domestic violence vary but the most common disorders seen in these children include depression, anxiety, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, substance abuse disorder, conduct disorder, and PTSD.[13] Notably, one study showed that 13% of children who witnessed domestic violence qualified for a full PTSD diagnosis and more than half displayed a number of PTSD symptoms, despite not fully meeting the criteria for diagnosis.[14] Studies have also indicated that significant disengagement from education and social isolation are common among children who witness domestic violence.[15]

Children’s relationships with their parents can also change due to domestic violence in the home.[16] It is fairly common for the direct victim of the abuse to be so focused on their own trauma that they don’t realize their child was present for the abuse, leading to neglect, harsher parenting, and a lack of necessary treatment for the child.[17] Research indicates that only 15% of children who witness domestic violence are connected with services.[18]

This change in the parental relationship can also lead to premature adultification of the child.[19] The term adultification refers to when children display behaviors typically shown by adults prematurely because of a trauma they experienced.[20] The most common adultification tendency brought on by witnessing domestic violence is the child intervening to protect their mother during an altercation with their father by interrupting verbally or physically putting themself between their parents.[21] Similarly, older children often tried to shield their younger siblings from witnessing the abuse by barricading them into rooms, distracting them, or by standing between their fathers and younger siblings during moments of conflict.[22]

Children who witness domestic violence are unfortunately likely to become direct victims of abuse themselves, as both the victim and the perpetrator of the initial violence are more likely to abuse their child than other parents.[23] Perpetrators are also likely to guilt and manipulate their shared children into not reporting the abuse by threatening family dissolution or legal complications.[24]

Though victims of domestic violence are not always aware of their child’s exposure to the violence, research shows that when women are aware that their children have been impacted by the violence, they are more likely to seek legal remedy through criminal or civil court.[25] However, some women have indicated that the opposite is true and that they avoided seeking criminal charges out of fear that testifying in court will retraumatize the child.[26] Once victims made the decision to move forward and report abuse, children were found to be a motivating factor for victims to maintain direct contact with the prosecutor working on the case.[27]

It is clear that concern over the court system’s treatment of the children of domestic violence survivors plays a large part in whether police officers and prosecutors even have the opportunity to bring charges against perpetrators.[28] To make things more accessible for children that may be involved in the legal system, some jurisdictions like the state of Colorado, have implemented programs that alleviate stress on child witnesses or eliminate the need for them to be in court at all.[29] One of these is the practice of sending police officers to domestic violence calls with a video camera and other supplies to gather additional evidence at the scene in order to avoid needing the child’s testimony later.[30]

Colorado has also created a Victims Witness Advocate unit that specializes in working with children to ensure that each child involved in the legal system has one consistent advocate to help them through every part of the process, from investigation to sentencing, which can help to reduce the fear, anxiety, and uncertainty that surrounds the legal process.[31] The results of implementing this program have indicated a decrease in trauma among child witnesses.[32] More generally, there are some evidence rules that allow for exceptions for child witnesses to make their time in the legal process easier and less traumatic.[33] However, those like the hearsay exception for victims of sexual abuse only apply to direct child victims of abuse, not child witnesses of domestic violence.[34]

The United States’ Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) was enacted in 1994 and it provides federal funds and resources to aid community responses to domestic violence crimes.[35] VAWA has significantly improved the services available to victims of domestic violence and has also led to the creation of more or improved resources and training for law enforcement, prosecutors, judges, health professionals, and victim advocates so these professionals are aware of how best to help victims.[36]

However, despite the strides made by VAWA for the direct victims of domestic violence, it does little to encourage help for child witnesses of domestic violence.[37] In October 2001, the United States Senate introduced a bill titled “Children Who Witness Domestic Violence Act” that was meant to highlight the unique situation of children who witness domestic violence and subsequently reduce the negative impacts to children by providing essential resources.[38] The act was also seeking to increase cooperation with different organizations, agencies, law enforcement and prosecutor offices, and healthcare workers to ensure children receive proper treatment.[39] Unfortunately, after being read aloud in the Senate, it was sent to the Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, where it has sat untouched since October 2nd, 2001.[40]

The federal government has codified a section on child abuse generally that briefly mentions child witness’s rights as well.[41] While this statute does implement a number of the same practices that have been successful in Colorado, there is a distinct lack of out of court support that is needed to ensure other advocates for domestic violence survivors in the community are able to work collaboratively with police and prosecutors.[42] States also have more work to do in implementing these statutes.[43] A recent survey of the fifty states and the District of Columbia in the United States indicated that only thirty-one states have enacted legislation that addresses domestic violence committed in the presence of children.[44]

These laws commonly impose stricter sentences to those convicted of domestic violence if a child witnessed the abuse.[45] This includes doubling the minimum or maximum terms of imprisonment or instructing the judge to consider the child’s experience witnessing the abuse as an aggravating factor.[46] Though less common, some states have laws that require an additional charge for the perpetrator, like child endangerment, or require the perpetrator to enter a counseling program, complete a period of supervised parenting, or even pay for the child witness’s counseling.[47] The increased punishments that perpetrators face under these laws are intended to illustrate to society that the behavior is unacceptable.[48] However, often most important is the assistance and support these laws provide to the children who witness domestic violence, such as providing funds for therapy or other counseling services.[49]

These laws are most successful when they are implemented immediately through a community effort, with those close to children and trained professionals working together to improve outcomes.[50] Some studies have shown that the more children are connected to a stable community, the less witnessing domestic violence impacts them.[51] A good example of this type of community response in action is a program implemented at Illinois State University, called For Children’s Sake.[52] This program was created in collaboration with the local battered women’s shelter after recognizing a need to serve the traumatized children also seeking shelter.[53] For Child’s Sake accepts referrals from the shelter and other community partners and provides therapy free of charge to child witnesses of domestic violence.[54] The program also offers other interventions, such as violence prevention and problem-solving services.[55]

Progress for child witnesses of domestic violence has been slow, with few programs like this being implemented despite decades of data indicating the severe harm that falls on children who witness domestic violence. To combat this, the legal system as a whole ought to avoid bringing children into domestic violence proceedings whenever possible. The current exceptions for hearsay that protect children victims of crimes are certainly important but need to be extended to child witnesses of domestic violence, as these children experience similar psychological symptoms and levels of trauma. Being forced to take the stand to testify about the inter-parental violence they witnessed firsthand forces them to relive their experience and leads to retraumatization.[56]

Federal and state governments also need to enact legislation that prioritizes child witnesses of domestic violence when determining punishments for perpetrators. Though some states have already begun this process, all remaining states ought to follow in their footsteps, as should the federal government, for a more unified response. Not only would this create more awareness about the impacts on child witnesses, but it would provide an avenue for treatment for these children if the perpetrator is made to pay for their counseling or other services.

Additionally, the type of collaborative community response done by For Children’s Sake is essential to improving outcomes for child witnesses of domestic violence. These responses should be a part of the various state and federal laws that are implemented. Mandating communication between police, prosecutors, schools, parents, mental health and medical professionals, and other relevant organizations is an important step in this collaborative response.

With more funding, professionals and other actors can provide child witnesses to domestic violence with necessary resources and counseling to move past these traumatic experiences and improve outcomes. Numerous therapies have been shown to help with the psychological symptoms child witnesses to domestic violence experience, but their effectiveness is often highly individualized, depending heavily on the personality of the child to determine which treatment is best suited to their needs. Providing communities, organizations, medical professionals, and caregivers with funds will allow them to work collaboratively in finding what works best for each child. These improved outcomes will hopefully decrease the likelihood that the children who witness domestic violence will go on to be abused or perpetuate violence themselves as adults.

—

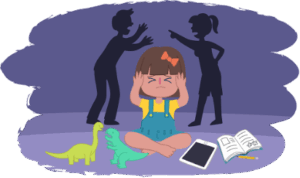

[1] Illustration of a child reacting to her parents fighting, in Families Impacted by Domestic Violence, KidsHelpline (2026), https://kidshelpline.com.au/parents/issues/families-impacted-domestic-violence.

[2] See generally, Nancy Lemon, Domestic Violence Law (6th ed. 2024).

[3] Id.

[4] Keir Starmer, Domestic Violence: The Facts, the Issues, the Future, 25 Int’l Rev. L., Computs. & Tech., 9, 11 (2011).

[5] Karin v. Rhodes et. al., “I Didn’t Want to Put Them Through That”: The Influence of Children on Victim Decision-Making in Intimate Partner Violence Cases, 25 J. Fam. Viol., 485–86 (2010).

[6] Einat Peled, The Battered Women’s Movement Response to Children of Battered Women, 3 Viol. Against Women, 424 (1997).

[7] Sue Abell, Domestic Violence: Its Impact on Children, 47 Clinical Pediatrics, 413, 414 (2008).

[8] Yuk-Chung Chan & Jerf Wai-Keung Yeung, Children Living With Violence Within the Family and Its Sequel: A Meta-Analysis From 1995-2006, 14 Aggression & Violent Behav., 313, 314 (2009).

[9] Abell, supra note 6, at 413; Matthias Brockstedt et. al., The Impact of Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault on Family Dynamics and Child Development: A Comprehensive Review, 60 Turk. Arch. Pediatr. 5 (2025).

[10] Abell, supra note 6, at 385; Jennifer McIntosh, Children Living with Domestic Violence: Research Foundations for Early Intervention, 9 J. Fam. Stud., 219, 224 (2003); Joseph J. Coyne et. al., Threat Vigilance in Child Witnesses of Domestic Violence: A Pilot Study Utilizing the Ambiguous Situations Paradigm, 9 J. Child & Fam. Stud., 377, 385 (2000).

[11] Umbreen Feroz et. al., Role of Early Exposure to Domestic Violence in Display of Aggression among University Students, 30 Pak. J. Psych. Rsch, 323, 335 (2015).

[12] Abell, supra note 6, at 413; Feroz et. al., supra note 10, at 324.

[13] Victoria Olubola Adeyele & Veronica Ibitola Makinde, Mental Health Disorder as a Risk Factor for Domestic Violence Experienced by School Children, 28 Mental Health Rev. J., 414 (2023).

[14] Graham-Berman & Alytia A. Levendosky, Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Children of Battered Women, 13 J. Interpersonal Viol., 5 (1998).

[15] Adeyele, supra note 12, at 416; Rebecca Stewart et. al., Examining the Impact of Domestic and Family Violence on Young Australians’ School-Level Education, 1, 11 Austl. J. Soc. Issues, 1 (2025).

[16] Alicia F. Lieberman et. al., Toward Evidence-Based Treatment: Child-Parent Psychotherapy with Preschoolers Exposed to Marital Violence, 44 J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, 1242 (2005); Jeffrey L. Edleson, Children’s Witnessing of Adult Domestic Violence, 14 J. Interpersonal Viol., 839, 841 (1999).

[17] Lieberman et. al., supra note 15, at 1242; Graham-Berman et. al., supra note 13, at 6; Edleson, supra note 15 at 843–44.

[18] Einat Peled, The Battered Women’s Movement Response to Children of Battered Women, 3 Viol. Against Women, 424, 425 (1997).

[19] Megan L. Haselschwerdt & Caroline Tunkle, Adultification in the Context of Childhood Exposure to Domestic Violence, 87 J. Marriage & Fam., 346, 355 (2025).

[20] Id.

[21] Id.

[22] Id. at 357.

[23] Einat Peled, Abused Women Who Abuse Their Children: A Critical Review of the Literature, 16 Aggression & Violent Behavior, 325, 325–26 (2011); Peled, supra note 17, at 428. (1997).

[24] Edleson, supra note 15, at 841.

[25] Karin Verlaine Rhodes et. al., The Impact of Children in Legal Actions Taken by Women Victims of Intimate Partner Violence, 26 J. Fam. Viol., 355, 356 (2011).

[26] Id. at 356-57.

[27] Id. at 363.

[28] Id.

[29] Kathleen Shoen, Kids and Court, 33 Colorado Lawyer, 31 (2004).

[30] Id.

[31] Id.

[32] Id.

[33] Id. at 32.

[34] Shoen, supra note 28, at 32; Child Hearsay: When Can We Use It?, The Manely Firm, P.C. (June 9, 2024), https://www.allfamilylaw.com/2024/06/child-hearsay-when-can-we-use-it/.

[35] Violence Against Women Act, National Network to End Domestic Violence, https://nnedv.org/content/violence-against-women-act/# (last visited Oct. 29, 2025).

[36] History of the Violence Against Women Act, Legal Momentum, https://www.legalmomentum.org/history-vawa (last visited Oct. 29, 2025).

[37] See Id.

[38] S.1483, 107th, Children Who Witness Domestic Violence Act (2001).

[39] Id.

[40] Id.

[41] 18 U.S.C § 3509 (1984).

[42] 18 U.S.C § 3509 (1984); Shoen, supra note 28 at 31.

[43] Erica Cook Reott et. al., State Laws on Intimate Partner Violence Witnessed by Children in the United States, 46 J. Public Health Policy, 284 (2025).

[44] Id.

[45] Id. at 287.

[46] Id. at 287-91.

[47] Id. at 291.

[48] Id.

[49] Id.

[50] Kym L. Kilpatrick & L. M. Williams, Potential Mediators of Post-Traumatic Disorder in Child Witnesses to Domestic Violence, 22 Child Abuse & Neglect 319, 328 (1998); McIntosh, supra note 9 at 230.

[51] Judith A. Wolfer et. al., The Kids Are Not All Right, Maryland Bar Journal 4, 10 (Jan. 2012).

[52] Connie Burrows Horton et. al., For Children’s Sake: Training Students in the Treatment of Child Witnesses of Domestic Violence, 30 Prof. Psych.: Rsch. & Prac., 88 (1999).

[53] Id.

[54] Id.

[55] Id. at 89.

[56] Robert H. Pantell, The Child Witness in the Courtroom, 139 Am. Acad. of Pediatrics, 1, 4–5 (2017).