Written By Maria Pittella L’27

The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization[1] further entrenches social and economic inequalities into the American legal system by creating what I term geographical “rights deserts,” thereby hindering minority communities. In a post-Dobbs America, women—particularly low-income and minority women—are facing unprecedented legal barriers to accessing abortion and health care. In this context, the Dobbs ruling created rights deserts for poor minority women who want and need abortions but cannot afford to travel to get one. However, states continue to restrict access to abortion by prohibiting the use of telehealth medicine to prescribe abortion medication.[2] Therefore, abortion tourism may be the only way women in states with abortion bans can access safe and legal abortions. Particularly, Virginia—the only southern state that allows abortion up until the third trimester[3]—can serve as the last safe haven of the South for impoverished women to access safe and legal abortions.

The Effects of Dobbs

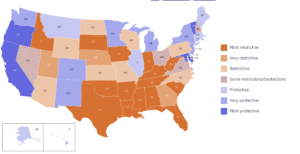

The Dobbs ruling aggravated the cycles of institutionalized degradation and poverty by restricting access to abortion. The mechanisms established leading up to and after the Dobbs ruling contribute to rights deserts—geological pockets where citizens of a particular area or region are denied access to rights and are unable to move to other states that would afford them those rights. Forty-one states have some form of abortion bans, with twelve banning abortion completely.[4] Regarding abortion access, these rights deserts cause economic harm and significantly burden poor minority women.[5]

Intrastate

Access to telehealth and medication abortion allows women in rights deserts to safely terminate their pregnancies without having to leave the state. Many abortion clinics are forced to close when states ban or restrict access to abortion.[6] Between 2020 and March 2024, a total of sixty-three in-person clinics closed in states with total abortion bans.[7] In light of these restrictions on abortion access, women are now turning to medication abortion and telehealth.[8] After the Dobbs ruling, demand for telehealth medication abortion increased in many states.[9] Studies show that telehealth is particularly useful for populations facing systemic barriers, such as low-income women.[10] The Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) has approved mifepristone for use through ten weeks, and the 2024 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine allows providers to continue to prescribe the medication without additional restrictions.[11] According to recent studies, telehealth abortions account for about twenty-five percent of all abortions[12] and almost two-thirds of all clinician-assisted abortions are done through medication.[13] Medication abortions have increased by thirty-two percent between 2020 and 2023.[14] This shift demonstrates the need for abortion access in rights deserts where physical clinics no longer exist.

Some states, however, are trying to place strict prohibitions on abortion medications or ban them all together.[15] Nine states—six of which have total abortion bans—currently prohibit the use of telehealth to prescribe and/or mail medication abortion.[16] Additionally, three states are seeking to reinstate the requirements for in-person dispensing requirement and three in-person visits—effectively prohibiting the use of telehealth for medication abortion.[17] These restrictions would further harm women living in rights deserts by completely denying them access to abortion care in their state.

Interstate

As states enact abortion restrictions or bans, abortion tourism—traveling to obtain an abortion in a state where it is legal[18]—has also increased in the years following Dobbs.[19] But not all women have the means to travel. Studies indicate that minority women’s abortion timing and access will be “disproportionately impacted” if states continue to pass laws limiting the quantity of abortion providers.[20] Women in states with abortion bans were more likely to face delays due to the associated cost of travel to obtain an abortion.[21] Since Dobbs, travel costs have increased from an average of $179 to $372.[22] Moreover, residents from abortion-ban states saw a dramatic increase in travel time compared with abortion access before a ban, increasing from 2.8 hours to 11.3 hours.[23] Even though funding for travel assistance may be available through various non-profits, many people are unaware of how to access and use this funding.[24]

Additionally, states are enacting news laws to combat legal repercussions for those seeking, facilitating, and assisting those seeking abortion.[25] Shield laws prohibit state officials from cooperating with certain requests or orders from other states regarding the identification of women who used telehealth services to obtain abortion medication.[26] As of October 2025, twenty-two states and D.C. provide protections against out-of-state investigations and prosecutions for reproductive health care.[27] Furthermore, eight states have provisions that explicitly protect patients regardless of their location, allowing them to access telehealth care.[28] These shield laws offer protections for patients that would not otherwise be able to have a safe abortion.

Virginia’s Role

Geography is power, and Virginia has just that. Virginia’s less restrictive abortion laws may allow women from other southern states with more restrictive policies to gain access to abortions. Recent data shows that as the number of abortions in states with a ban decrease, a considerate number of women travel to other states to get an abortion.[29] Southern states have some of the most restrictive laws against abortion.[30] Virginia, however, is the only southern state to permit abortion up until the third trimester.[31] In Virginia from June 2022 through March 2024, telehealth abortions increased by over fifty percent and in-person abortions rose by thirteen percent.[32] Over 9,000 women traveled into Virginia in 2024 to get an abortion.[33]

Moreover, Virginia has an opportunity to enshrine the right to reproductive freedom into the state constitution. In 2025, the Virginia General Assembly voted in favor of a Constitutional amendment codifying an individual’s “fundamental right to reproductive freedom, including the ability to make and carry out decisions relating to one’s own prenatal care, childbirth, postpartum care, contraception, abortion care, miscarriage management, and fertility care.”[34] The vote allows the amendment to move onto the next step in the process, where the General Assembly will vote again on the amendment in 2026 before it appears on the November 2026 ballot.[35] Additionally, Virginia’s new Governor-elect, Abigail Spanberger, has shared her commitment to abortion access for all.[36] Virginia can help women in rights deserts gain access to abortions by enacting shield laws and proving funding for low-income out-of-state women seeking abortions.

Conclusion

In a post-Dobbs America, states have the power to protect abortion rights and stop the cycles of harm minority women face. For women in states with abortion bans, traveling out of state may be their only option for obtaining safe and legal abortions. States like Virginia allow women to get abortions when they otherwise would not have been able to. But the economic barriers to travel prevent poor women from exercising their right to movement. Organizations—like the Brigid Alliance—offer economic and emotional support to women who face logistical challenges to accessing abortion. These financial resources provide low-income women with the assistance needed to access abortions. Virginia has a unique position, both geographically and socially, where low-income women from the south may be able to gain access to abortion when they otherwise would not. Virginia must take this opportunity to protect reproductive rights by enacting the Constitutional amendment.

—

[1] 597 U.S. 215 (2022).

[2] See Laurie Sobel et al., The Intersection of State and Federal Policies on Access to Medication Abortion Via Telehealth after Dobbs, KFF (Jul. 24, 2025) https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/the-intersection-of-state-and-federal-policies-on-access-to-medication-abortion-via-telehealth-after-dobbs/.

[3] Va. Code § 18.2-73.

[4] Talia Curham, State Bans on Abortion Throughout Pregnancy as of July 7, 2025, Guttmacher Institute (Ed. Peter Ephross) (2025) https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/state-policies-abortion-bans.

[5] See Alexa L. Solazzo, Different and Not Equal: The Uneven Association of Race, Poverty, and Abortion Laws on Abortion Timing, 66 Soc. Probs. 519, 542 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spy015.

[6] See Rachel K. Jones et al., The Number of Brick-and-Mortar Abortion Clinics Drops, as US Abortion Rate Rises: New Data Underscore the Need for Policies that Support Providers, Guttmacher Institute (Sept. 30, 2025), https://www.guttmacher.org/report/abortion-clinics-united-states-2020-2024.

[7] See id.

[8] See Karen Diep, Abortion Trends Before and After Dobbs, KFF (Jul. 15, 2025) https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/abortion-trends-before-and-after-dobbs/.

[9] See Anna E. Fiastro, Demand for Medication Abortion Through Telehealth Before and After the Dobbs v. Jackson Supreme Court Decision in States Where Abortion Is Legal, 35 Women’s Health Issues 324, 328 (June 20, 2025), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2025.06.003.

[10] Id.

[11] See generally 602 U.S. 367 (2024).

[12] See Diep, supra note 7.

[13] See Amy Friedrich-Karnik et al., Medication Abortion Remains Critical to State Abortion Provision as Attacks on Access Persist, Guttmacher Institute (May 7, 2025), https://www.guttmacher.org/2025/02/medication-abortion-remains-critical-state-abortion-provision-attacks-access-persist.

[14] Isabel DoCampo et al., The Role of Medication Abortion Provision in US States Without Total Abortion Bans, 2023, 57 Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 3, 5 (Feb. 10, 2025), https://doi.org/10.1111/psrh.12294.

[15] See Sobel et al., supra note 2.

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] See Marissa Postell, What is Abortion Tourism?, Ethics & Religious Liberty Comm’n (Apr. 5, 2022) https://erlc.com/resource/what-is-abortion-tourism/.

[19] See Kate Zernike & Adam Liptak, Texas Supreme Court Shuts Down Final Challenge to Abortion Law, N.Y. Times (Mar. 11, 2022) (noting that while “Texas law cut the number of abortions in the state by 60 percent[,] Planned Parenthood clinics in neighboring states have reported an 800 percent increase in women seeking abortions” after the Supreme Court shut down a federal challenge to the state’s ban on abortion).

[20] Solazzo, supra note 4, at 539.

[21] Nancy F. Berglas et al, Changes in Abortion Access, Travel, and Cost Since the Implementation of State Abortion Bans, 2022-2024, 115 Am. J. Pub. Health 1173, 1173 (2025) https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2025.308191.

[22] Id.

[23] Id.

[24] See id.

[25] See Anna Bernstein et al., Attacks on Shield Laws Are the Next Step in Criminalizing Abortion Care, Guttmacher Institute (Sep. 10, 2025), https://www.guttmacher.org/2025/09/attacks-shield-laws-are-next-step-criminalizing-abortion-care.

[26] Kimya Forouzan, Shield Laws Related to Sexual and Reproductive Care, Guttmacher Institute (Oct. 20, 2025) https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/shield-laws-sexual-and-reproductive-health-care.

[27] Shield Laws for Reproductive and Gender-Affirming Health Care: A State Law Guide, UCLA Law (last visited Oct. 20, 2025), https://law.ucla.edu/academics/centers/center-reproductive-health-law-and-policy/shield-laws-reproductive-and-gender-affirming-health-care-state-law-guide.

[28] Id.

[29] Berglas et al., supra note 18, at 1173.

[30] See Interactive Map: US Abortion Policies and Access After Roe, Guttmacher Institute (Oct. 22, 2025) https://states.guttmacher.org/policies/?_gl=1*1nggmwa*_gcl_au*OTg2NDU3NDY4LjE3NTk1MDE0MDg.*_ga*MTYwMzU3NTEzNy4xNzU5NTAxNDA4*_ga_PYBTC04SP5*czE3NjIxOTM5OTUkbzkkZzEkdDE3NjIxOTQwNDAkajE1JGwwJGgw.

[31] Id.

[32] Julia Rollison et al., Understanding the State and Local Policies Affecting Abortion Care Administration, Access, and Delivery: A Case Study in Virginia, RAND Health Q. (2024) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11630096/.

[33] Monthly Abortion Provision Study, Guttmacher Institute (last visited Nov. 7, 2025), https://www.guttmacher.org/monthly-abortion-provision-study#interstate-travel.

[34] 2025 Va. Acts Ch. 603.

[35] In a Historic Vote, Constitutional Amendment to Protect Reproductive Freedom Passes the General Assembly, Am. Civil Liberties Union (Feb. 13, 2025) https://www.acluva.org/press-releases/historic-vote-constitutional-amendment-protect-reproductive-freedom-passes-general/.

[36] See Defending Reproductive Freedom, Spanberger for Governor (last visited Nov. 7, 2025), https://abigailspanberger.com/issue/defending-reproductive-freedom/.