Written by Sara Arora, L’26

The first Amendment is a cornerstone of the functioning of the American system of democracy. During the development and ratification of the Constitution, Anti-Federalists had concerns that without a bill of rights, the federal government would wrest liberty from the people. [1] After much debate, twelve amendments to the constitution were proposed and ten were ratified as the Bill of Rights.[2] The rights covered in the First Amendment–free religion, speech, press, and assembly–reflect the idea that a functional society grows with the exchange of ideas and challenges to power.[3] However, free speech has been bound by limitations since its ratification; often, these limitations materialize when there are perceived dangers from the particular kind of speech in question.[4] The First Amendment also protects the right to peaceably assemble and petition the government to address grievances[5] The limitations on protest, information, and speech are especially visible through the lens of American involvement in imperialist foreign conflicts. Two notable case studies can illuminate how and when the government intervenes to limit these acts: The Vietnam War Era and the Post-October 7, 2023 Free Palestine period. When the United States is involved in imperialist foreign conflicts, the government tightens limits on the speech and protest rights that the First Amendment purports to protect.

Vietnam War Era

The Vietnam war grew out of divisions and conflict between North and South Vietnam after France withdrew its imperialist forces from the region.[6] During this period, South Vietnam began to consolidate its power; Diem, the leader of South Vietnam, then declared himself President of the Republic of Vietnam in 1955.[7] At this point, American military forces, policy counsel, and financial aid were given in support of this democratic project.[8] The American imperialist project across the post-colonial world focused on exporting capitalist and democratic systems through logistics.[9] Efforts involving military campaigns, trade integration, and financial aid were targeted at integrating Vietnam into the American sphere of influence and control.[10] Issues with administration, suppression, and a growing support of communist leadership contributed to escalating tensions with North Vietnam, and by 1965 the US had sent 3,500 troops into Vietnam.[11]

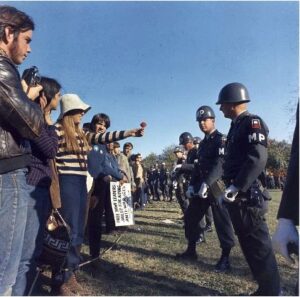

In 1965, the United States began continually bombing North Vietnam, at which point troop levels and the combat death toll had risen significantly which resulted in growing antiwar sentiment.[12] The public were seeing atrocities, gruesome deaths, and devastation on their televisions.[13] Everyone knew someone who had served, and most people knew someone who had died.[14] Protests grew around the country on university campuses and in other public spaces.[15] In October 1967, the March on the Pentagon included at least 20,000 protestors.[16] This protest, a strong showing of solidarity, was met with 647 arrests and 47 serious injuries.[17] Antiwar protests were met with resistance and violence by the State, none more famous than the Kent State University protest.[18] This protest was one of many student organized protests on university campuses.[19] Unlike others of its kind, the national guard were on the scene and began firing on both student protestors and observers.[20] The national guard killed four students and grievously injured nine.[21] State action against public antiwar protests did not occur in a vacuum; the critique of American involvement in Vietnam tied to mass deaths and cries for humanity stemmed from widespread coverage of the atrocities of the war and the death toll on television.[22]

Schenck v. United States

Schenk v. United States was decided in 1919 and centered around resistance to the draft in World War I.[23] The two defendants were members of the executive committee of the socialist party and were convicted under the Espionage Act for circulating leaflets that encouraged men to avoid the draft.[24] The flyers warned that conscription made free men into subjects, forced them to kill against their will, and deprived them of the liberties of the Constitution.[25] The leaflets encouraged men to assert their rights and made a 13th Amendment-style argument that the draft was forced servitude and the Constitution protects against that.[26] The defendants in Schenk argued that this speech contained in the leaflets was protected under the First Amendment.[27] In his opinion, Justice Holmes admitted that the statements in the leaflets would ordinarily be constitutionally protected and that none of them violated the norms of free speech.[28] However, the speech in wartime may well have presented an actual obstruction to recruitment for the war and its efforts.[29]As such, Justice Holmes stated that, when words present a clear and present danger of illegal activity (draft dodging), they are not protected under the First Amendment.[30]

This decision was eventually overturned but its precedent was key and iterative to many later cases on free speech and the antagonistic sentiment towards antiwar protests continued in the Court. [31] In 1951, the standard changed to “clear and probable danger” in Dennis v. United States, a case where communists were convicted for attempting to advocate for a violent overthrow of the United States government.[32] The Court upheld these convictions under this standard, which purported to weigh the gravity of the danger and its improbability to decide if it justified an invasion of free speech to avoid that danger.[33] The standard changed again to “imminent lawless action” in the late 1960s with the decision in Brandenburg v. Ohio[34] Regardless of the evolving standard and the overturning of the case, Schenk remains an example of free speech restrictions in wartime and its adjacent contexts.[35]

This sentiment tracks through United States v. O’Brien, a case concerning protesters burning their draft registration cards outside of the South Boston Courthouse during the Vietnam War.[36] The court upheld the law against mutilating or destroying draft cards under the Universal Military Training and Service Act. [37] O’Brien argued that the statutory amendment he was charged under infringed on free speech, had no real legislative aim, and thus was unconstitutional. [38] O’Brien argued that he used his speech to fairly protest the Vietnam War by burning the draft card.[39] The Court ultimately decided, however, that the amendment in question did not on its face abridge free speech and was therefore constitutional.[40] This case presented a new test for acceptable abridgement of first amendment rights: the government must have a compelling interest in regulating a nonspeech element which, when combined with the speech, may result in the restriction of that speech.[41]

Ultimately, the Vietnam War Era, its speech jurisprudence, protests, and information spread, provide a snapshot of limitations on protest rights tied to American involvement in an imperialist foreign conflict.

Post-October 7, 2023 Free Palestine Period:

American discourse on colonialism and conflict in Palestine and Israel was explosively revitalized during and after the attack that took place on October 7, 2023.[42] This attack, as well as the continual reaction from Israel that has resulted in a humanitarian crisis, has reignited discourse and protest around the issue.[43] Protest and speech in support of a free Palestine, however, has been a part of the American political sphere for decades.[44] This staying power and cycles of attention correlate with the longevity of the conflict and colonial project in the Palestinian lands. [45]

After WWII, the British Empire held in mandate the Palestinian territories, parts of which it promised to Jewish people who had been displaced by the war.[46] The armed territorial disputes that followed began the modern conflict between Israel and Palestine.[47] The 1947 United Nations partition plan split the territory into what has been recognized today as Palestine and Israel. In 1948, Israel declared itself an independent state, and subsequently enacted the “Nakba”, a mass displacement of Palestinians from their homes and land.[48] The ongoing history and context surrounding the conflict between Palestine and Israel are complex, but Israel has been illegally occupying Palestinian territory for over fifty-five years.[49] In 2022, the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian Territory reported that this occupation was indistinguishable from settler colonialism.[50] In short, the speech and protest efforts (and counter-efforts) surrounding Palestine and Israel did not begin on October 7, 2023, but rather gained increased attention.[51]

This period of speech and protest for Palestine embodies several goals, including an end to the ongoing violence, self-determination for the Palestinian people, and institutional divestments.[52] Since October 7, 2023, when the “War in Gaza” became more sharply visible, people have seen graphic devastation and violence on their newsfeeds and phone screens.[53] As with the Vietnam War, a significant force for pro-Palestinian advocacy and protest against the involvement of the United States in the current conflict have stemmed from student activism.[54] Encampments on university campuses demanding institutional divestment from Israel have been sweeping the United States; thousands of arrests have been made across campuses for these protests.[55] One such example is a protest at the University of Texas at Austin, where no encampment was planned but police still showed up.[56] The police, equipped in full riot gear, escalated tensions, tackled students, utilized violence, and arrested several students and other protestors.[57] This protest presents an interesting First Amendment discussion since it was a public assembly on public property and therefore subject to the First Amendment and local laws surrounding public assembly.[58]

Outside university campuses, people have been organizing mass protests across the country including at the Capitol.[59] One protest outside the White House called for a ceasefire, while another sit-in protest took place in the Capitol building ahead of Netanyahu’s congressional address.[60] Calls for a ceasefire and for the United States to stop supplying arms and funds to Israel have been coming from around the country and go hand-in-hand with a revitalisation of the boycott movement.[61]

Boycotts as a strategy for protest and leveraging economic pressure for social change is not new, and have been used in the past for Palestinian advocacy. In turn, government action against boycotts are also well-established..[62] In 2019, the Senate passed The Combating BDS Act of 2019.[63] This Act would allow state and local governments to require government contractors from public school teachers to companies to certify that they are not participating in politically motivated boycotts against Israel.[64] As notoriety and visibility of boycotts of Israel increased after October 7, 2023, more congressional action in opposition to these boycotts was taken. In September of 2024, the Anti-BDS Labeling Act was passed in the House and referred to the Senate.[65] This Act intended to permanently codify a regulation from the Federal Register to label goods from most of the Occupied West Bank as products of Israel and labeled products from the West Bank and from Gaza separately.[66] This would make it harder for consumers to boycott products from Israel.

There has been government action concerning protests and assembly for Palestine as well. One of many cases from the Supreme Court during the summer of 2024 contains a deliberate line and grave implications for the potential criminalisation of assembly and presence in public places.[67]

Grants Pass v. Johnson:

Grants Pass v. Johnson is a case that, at its face, seems to concern homelessness and the constitutionality of laws that criminalize sleeping in public places.[68] The implications of the discussion and the holding, however, reach farther than criminal penalties for people experiencing homelessness.[69] The law challenged in Grants Pass criminalized overnight presence and encampment in public spaces.[70] In responding to the assertion that the decision specifically targeted and criminalized homelessness, Justice Gorsuch wrote in the majority opinion: “Under the city’s laws, it makes no difference whether the charged defendant is homeless, a backpacker on vacation passing through town, or a student who abandons his dorm room to camp out in protest on the lawn of a municipal building.” [71] This inclusion and description of a student is pointed when considering the context of the student encampments, mass protests and sit-ins in support of a ceasefire and a free Palestine.[72] The decision declares the constitutionality of these strict laws concerning presence in public places as well as criminalizing violations of those laws.[73]

The pushback against speech in support of Palestine has not resulted in massive government action yet, but the foundations are present.[74] The Anti Defamation League (“ADL”) sent a letter to hundreds of university deans and presidents requesting that they investigate student activities associated with Students for Justice in Palestine (“SJP”) after an objectionable statement was made by SJP National.[75] The letter said to investigate these students for materially supporting terrorism; this allegation of material support for terrorism blurred the lines of protected speech and criminal action.[76] This request equates the views of all student members with the views of an organization they somewhat associate with, walks back the established protections of speech, and analogizes speech with material support.[77] The word “material” is meant to create a distinction between advocacy or beliefs and action; blurring this distinction invites the conflation of the two and therefore punishment for speech.[78] The existence of federal criminal laws prohibiting material support for terrorism makes this conflation dangerous.[79] In Florida, Governor Ron DeSantis has gone further and ordered SJP chapters to be disbanded at state universities which will likely lead to First Amendment litigation and bring these questions to the courts.[80]

In times of American involvement in imperialist foreign conflicts, the First Amendment often sees restriction. Over a century after its decision, Schenck v. United States remains visible in the limitations on the exercise of speech and assembly in wartime if American resources are involved.[81] The Vietnam War Era offers a lens into the beginning of modern public dissent of this kind, as well as the restrictive and sometimes violent way the government tried to quash it. As a protest movement of a similar kind is developing surrounding Israel’s war on and occupation in Palestine, it is easy to draw parallels between the two. The Vietnam War was the first televised war where the public could see combat and bombings from home.[82] The continuing attacks on Gaza may well go down as the first TikTok war. As limitations on speech, assembly, and protest continue to arise, it is important to ask ourselves what the First Amendment protects and how effective that protection is.

Wikimedia Commons, Vietnam-protest-flower-mp (photograph), (Oct. 21, 1967).

Jordan Vonderhaar, Demonstrators and Texas state troopers stand off during a pro-Palestinian protest at the University of Texas in Austin (photograph), (Apr. 24, 2024).

[1]See Nils Gilbertson, Return of the Skeptics: The Growing Role of the Anti-Federalists in Modern Constitutional Jurisprudence, 16 Georgetown J. of L. and Pub. Pol’y, 255, 261 (2018).

[2] The Bill of Rights: A Transcription, Nat’L Archives, https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/bill-of-rights-transcript

[3]See Edmond Cahn, The Firstness of the First Amendment, 65 Yale L. J., 464, 447.

[4]See Frederick Schauer, Harm(s) and the First Amendment, 2011 Sup. Ct. Rev., 81, 84

https://wwwjstororg.newman.richmond.edu/stable/10.1086/665583?searchText=importance+of+the+first+amendment&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Dimportance%2Bof%2Bthe%2Bfirst%2Bamendment%26so%3Drel&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&refreqid=fastly-default%3A6a9760ae910b9e8e78114b2a44b1c5a5&seq=4.

[5]See Edmond Cahn, The Firstness of the First Amendment, 65 Yale L. J., 464, 447.

[6] See Ronald H. Spector, French rule ended, Vietnam divided, Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/event/Vietnam-War/French-rule-ended-Vietnam-divided (last updated Oct. 27, 2024).

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] See Wesly Attewell, Just-in-Time Imperialism: The Logistics Revolution and the Vietnam War, Annals of the Ame. Ass. of Geographers, 1329, 1330, Nov. 10, 2020 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/24694452.2020.1813540?scroll=top&needAccess=true.

[10] Id

[11] See id.

[12] See Doug McAdam and Yang Su, The War at Home: Antiwar Protests and Congressional Voting, 1965 to 1973, Am. Socio. Rev., 697, 698 (2002). https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epdf/10.1177/000312240206700505

[13] See Robert K. Elder, Four Dead in Ohio: Fifty years ago, National Guard troops opened fire on unarmed Vietnam War protesters at Kent State University, sending shock waves across America, N. Y. Times Upfront (Feb. 17, 2020).

[14] Id.

[15]McAdam and Su, supra note 12 at 698

[16] See id.

[17] See id.

[18] See id.

[19] See id.

[20] See Robert K. Elder, Four Dead in Ohio’: Fifty years ago, National Guard troops opened fire on unarmed Vietnam War protesters at Kent State University, sending shock waves across America, N. Y. Times Upfront (Feb. 17, 2020).

[21] See id.

[22] See id.

[23] Id.

[24] Id. at 47, 49 (1919).

[25] See 5-4, Schenk v. United States, Prologue Projects, at 0:07:04 (Nov. 2023) https://www.fivefourpod.com/episodes/schenk-v-united-states/.

(Nov. 2023).

[26] See id.

[27] Id.

[28] Schenk, supra, note 26

[29] Id at 54.

[30] Prologue Projects, supra note 26 at 0:10:03.9 (Nov. 2023).

[31] Id at 0:13:09.5

[32] See id.

[33] Id at 0:14:01.6

[34] Id at 0:19:04.8

[35] See generally id.

[36] United States v. O’Brien, 391 U.S. 367, 369 (1968)

[37] See United States v. O’Brien, 391 U.S. 367, 370 (1968).

[38] See id.

[39] See generally, id.

[40] Id.

[41]Id at 376

[42] See, Jario I. Fúnez-Flores, The Coloniality of Academic Freedom and the Palestine Exception, Middle E. Critique, 465, 465 (July 7, 2024) https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/19436149.2024.2375918#abstract.

[43] See id.

[44] See id.

[45] Fúnez-Flores, Supra note 43.

[46] See The Question of Palestine, United Nations,https://www.un.org/unispal/history/

[47] See id.

[48]See Youssra Hamdan, Wartime Influencers: Palestinian citizen journalism on Instagram during the war on Gaza 2023-2024, 7 (2024) https://studenttheses.uu.nl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12932/47707/YH_Thesis_Wartime_Influencers_695263.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[49] See id.; Israel’s illegal occupation of Palestinian territory, tantamount to ‘settler-colonialism’: UN expert,United Nations (2022)https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/10/1129942.

[50] See id.

[51] Fúnez-Flores, supra note 43

[52] See Matt Egan and Ramishah Maruf, What the pro-Palestinian protesters on college campuses actually want, CNN, (April 26, 2024)https://www.cnn.com/2024/04/26/investing/what-pro-palestinian-protesters-want/index.html

[53] See Shooting deaths of fishermen, not “unique events” in Gaza, (aljazeeraenglish June 2024) https://www.tiktok.com/t/ZP889JJVb/; This girl in Gaza carried her sister over 2km on her shoulder, (ajplus Oct. 2024) https://www.tiktok.com/@ajplus/video/7428346768087125278?_r=1&_t=8qlGTP9UlNG.

[54] See, Mohamed Buheji and Aamir Hasan, ECHOES OF WAKE-UP Realising the Impact of The Seeds of Student Pro-Palestine Protests, Int’l. J. of Mgmt., 56, 57 (May is there a day? 2024). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/380533544_Echoes_of_Wake-up_Realising_the_Impact_of_the_Seeds_of_Student_Pro-Palestine_Protests.

[55] See id.

[56] See, 5-4, Free Rhiannon!, Prologue Projects at 0:09:26.6 (May. 2023) https://www.fivefourpod.com/episodes/free-rhiannon!-campus-protests-and-the-first-amendment/.

[57]Id at 0:18:00.5 – 0:22:41.5

[58] See, Scott Bomboy, The Constitutional Right to Protest at Universities (May 7, 2024) https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/the-constitutional-right-to-protest-at-universities.

[59] See, Voice of America, Thousands of pro-Palestinian protesters converge on US Capitol, YouTube (Aug. 2024) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EN47T4Q_TeI

[60] See, Forbes Breaking News, JUST IN: Pro-Palestine Protestors Surround White House Lawn In Protest Of War In Gaza, YouTube (June 2024) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=922nHwj-CCk; ABC News, Protesters on Capitol Hill call for cease-fire in Gaza YouTube (August 2023)https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2bERCjuyTBU.

[61] See, Mohamed Buheji and Dunya Ahmed Abdullah Ahmed, Keeping the Boycott Momentum- from ‘War on Gaza’ till ‘Free-Palestine’, Int’l. J. of Management, Dec. 2023, 205, 214, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376781097_Keeping_the_Boycott_Momentum-_from_%27War_on_Gaza%27_till_%27Free-Palestine%27

[62] See Combating BDS Act of 2019 S.1, 116th Cong. § 401-408 (2019).

[63] See id.

[64] See id; see also ACLU Comment on Senate Passage of S.1 and Combating BDS Act, ACLU (Feb. 5, 2019) https://www.aclu.org/press-releases/aclu-comment-senate-passage-s1-and-combating-bds-act.

[65]See H.R. 5179, 118th Cong. § 1-3 (2024).

[66] See id.; see also 85 Fed. Reg. 83984 (Dec. 23, 2020).

[67] See Grants Pass v. Johnson, No. 23–175, slip-op. 20 (S. Ct., June 28, 2024).

[68] See generally, Grants Pass v. Johnson No. 23–175, slip-op. (S. Ct., June 28, 2024). use id.

[69] Id.

[70]Id.

[71] Id at 20.

[72]Buheji and Hasan, supra note 55.

[73] Johnson, Supra note 68 at 31.

[74] Prologue Projects, supra note 26,

[75] Prologue Projects, supra note 26 at 0:26:24.4.

[76] Id at 0:26:24.4

[77] Id at 0:27:24.1

[78] Id at 0:29:40.7

[79] Id at 0:31:00.1

[80] Id at 0:41:12.6.

[81]Id; Schauer, supra note 4 at 84.

[82] See generally Michael Mandbelaum, Vietnam: The Television War, Print Culture and Video Culture, 157 https://www.jstor.org/stable/20024822.