By: Elizabeth Vanasse

When discussing the rights of students to enjoy free speech, the frequently cited case is Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District.[1] This case is heralded as the “high-water mark” of students’ rights to freely express themselves and to enjoy constitutional rights in the school-building.[2] However, the reality of Tinker is that its most progressive statement of student freedom is only dictum, not doctrine. Justice Fortas’s iconic line that students “do not shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate” is not binding law.[3] Further, cases following Tinker, even up to the most recent student speech case, Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L., emphasize Tinker’s vast shortcomings as the basis of students’ rights—and that it does not protect students the way it should.[4]

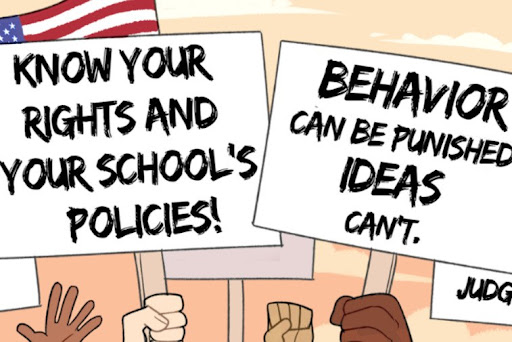

In Tinker v. Des Moines, the student speech being regulated was minimal and harmless: students were wearing black armbands to “publicize their objections to the hostilities in Vietnam.”[5] There was no actual disruption of school activities or any threat of disruption. The court determined the armbands were “‘pure speech’” and “entitled to comprehensive protection under the First Amendment.”[6] Despite that the court sided with the students and overruled the school’s attempts to shut down student speech, the question remains: what happens if student speech is not passive, not entirely “akin to pure speech,” and not entirely silent? Would the First Amendment still offer its protections?

Some scholars say no.[7] Tinker, in their view, does not robustly protect student speech. Tinker should not be famous for being pro-student: its “lasting precedent is not the principle that constitutional rights are still retained at the schoolhouse gate, but instead is its control discourse.”[8] Further, post-Tinker Supreme Court decisions have only narrowed the First Amendment protections for students exercising free speech rights in and out of schools.[9] Since Tinker, the Supreme Court has refused to protect lewd speech, speech referring to drugs, and writings on abortion.[10]

Most recently, the Supreme Court refused to define whether its locus of control extends to speech made off school property and outside regular school hours. In Mahanoy, the speech at issue was a Snapchat posted to a private “story,” which inadvertently came to the attention of school employees.[11] The Supreme Court decision, although in favor of the student and holding the Pennsylvania school violated the student’s First Amendment rights by punishing her for the Snapchat, still refused to categorically ban schools’ regulation of student speech outside of school, leaving the door open for even more constriction of free speech.[12]

The Supreme Court continues to say that schools are “nurseries of democracy”[13] and should allow students to express themselves—but has recent case law truly shown that fervor in its doctrine, or just in catchy, one-line dicta?

[1] Tinker v. Des Moines Indep. Cmty. Sch. Dist., 393 U.S. 503 (1969).

[2] What Has the Supreme Court Said About Free Expression?, Freedom Forum Institute, https://www.freedomforuminstitute.org/about/faq/what-has-the-supreme-court-said-about-free-expression/ (last visited Oct. 7, 2021).

[3] Mary-Rose Papandrea, The Great Unfulfilled Promise of Tinker, 105 Va. L. Rev. 159, 165 (2019).

[4] Mahanoy Area Sch. Dist. v. B.L., 141 S. Ct. 2038 (2021).

[5] Tinker, 393 U.S. at 504.

[6] Id. at 505-06.

[7] See generally Allison N. Sweeney, The Trouble with Tinker: An Examination of Student Free Speech in the Digital Age, 29 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 359 (2018); Brandon James Hooer, An Analysis of the Applicability of First Amendment Freedom of Speech Protections to Students in Public Schools, 30 U. La Verne L. Rev. 39 (2008); Scott A. Moss, The Overhyped Path from Tinker to Morse: How the Student Speech Cases Show the Limits of Supreme Court Decisions—for the Law and for the Litigants, 63 Fla. L. Rev. 1407 (2011).

[8] Amanda Harmon Cooley, Controlling Students and Teachers: The Increasing Constriction of Constitutional Rights in Public Education, 66 Baylor L. Rev. 235, 247 (2014).

[9] Id. at 248.

[10] See Bethel Sch. Dist. v. Fraser, 478 U.S. 675 (1986); Hazelwood Sch. Dist. v. Kuhlmeier, 484 U.S. 260 (1988); Morse v. Frederick, 551 U.S. 393 (2007).

[11] Mahanoy, 141 S. Ct. at 2042—43.

[12] Adam Liptak, Supreme Court Rules for Cheerleader Punished for Vulgar Snapchat Message, N.Y. Times (June 23, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/23/us/supreme-court-free-speech-cheerleader.html.

[13] Mahanoy, 141 S. Ct. at 2046.