By: Callie Keen

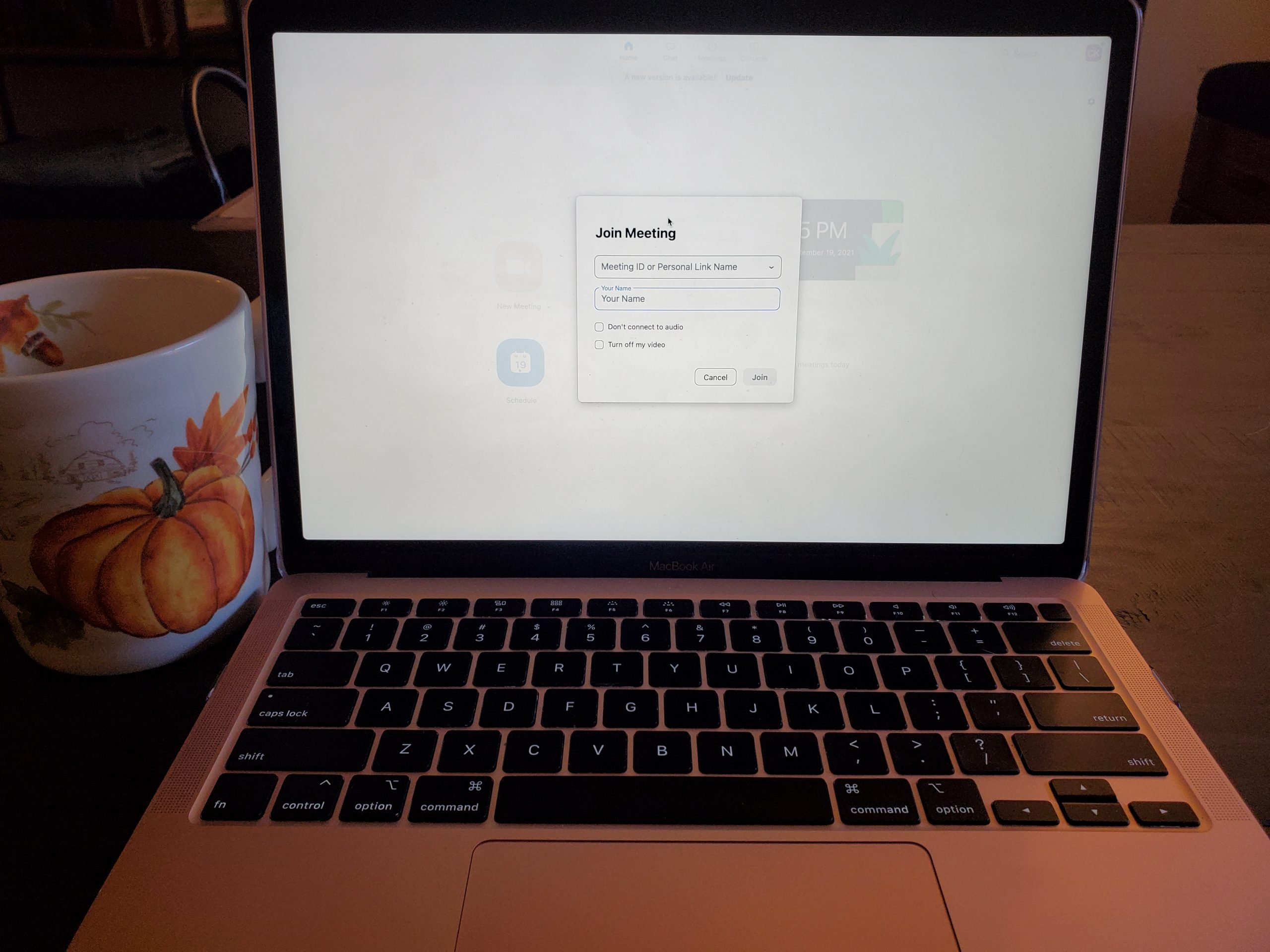

For many years, meetings of local and state public bodies – from school boards to city councils to state legislatures – have been hallmarked by engagement with interested citizens.[1] At these meetings, members of the public can closely watch the proceedings and offer their perspectives on proposals and community problems.[2] However, as COVID-19 swept through the United States, public bodies could no longer meet in-person.[3] Instead, they began holding meetings over Zoom, wherein interested citizens could attend the meetings and offer comments virtually.[4] With COVID-19 restrictions loosening in Virginia, the Virginia Freedom of Information Advisory (FOIA) Council is considering whether these electronic meetings should continue to be permitted.[5] In order to promote greater public participation in the governmental process and increase equitable representation in public bodies, legislation should be recommended by the FOIA Council that expands the use of electronic meetings by public bodies.

In Virginia, current statute generally requires in-person meetings for public bodies.[6] Individual members of public bodies may be permitted to participate electronically in narrow circumstances, such as illness or family emergency.[7] Further, members may not participate electronically more than twice a calendar year.[8] Throughout the past year, electronic public meetings were permitted regularly due to the formal state of emergency declared in Virginia as a result of the pandemic.[9] However, public bodies are expected to transition back to in-person meetings, as Virginia’s state of emergency expired on June 30, 2021.[10] In order to further allow for electronic meetings, the FOIA Council and Virginia General Assembly would have to amend the current statute in favor of expansion of electronic participation generally, not only during a state of emergency.

The FOIA Council should seek to amend the statute in this way, as electronic meetings contribute to increased public participation in the governmental process.[11] People unable to travel to meetings, those caring for sick family members at home, individuals unable to leave the house, and others can offer comment during meetings from wherever they happen to be.[12] This positive impact of electronic meetings on public participation was evident throughout the past year in Albemarle County, where the school board experienced record public engagement through virtual meetings.[13] While 15 to 20 community members reflected a strong turnout at in-person meetings, it became common practice for more than 1,000 people to attend and participate virtually.[14] This large increase in public participation demonstrates a crucial benefit of allowing public bodies to meet virtually.

Further, expanding the use of electronic meetings would likely open the door to public service for more people.[15] By eliminating certain logistical burdens, electronic meetings might improve access to public service for more women, people with disabilities, individuals with child care responsibilities, and people who cannot travel for in-person meetings in the middle of the work day.[16] FOIA Council Member Cullen Seltzer believes that many citizens who have a contribution to make are disqualified from public service when asked to be in-person all of the time.[17] He argues that essentially disbarring electronic meetings will leave voices out of leadership that ought to be heard.[18]

The FOIA Council and general public will likely continue to evaluate electronic meetings and their implications in the coming months.[19] Though the debate surrounding virtual public meetings may at first glance appear insignificant compared to other concerns, this issue implicates fundamental values of governance in the US. By encouraging the use of electronic meetings by public bodies in Virginia, we have the opportunity to heighten equitable representation in public service and increase public participation in our democratic process. We can preserve an effective practice learned during the pandemic and use it to strengthen local and state governance in Virginia today.

[1] David A. Lieb, Pandemic Redefines ‘Public’ Access to Government Meetings, AP News (Mar. 14, 2021), https://apnews.com/article/legislature-state-legislature-coronavirus-pandemic-4d6cf5821b44cb0ce70587305d5e1175.

[2] Lieb, supra note 1.

[3] Graham Moomaw & Sarah Vogelsong, Governance Via Zoom Is Coming to an End. Should It?, Virginia Mercury (June 28, 2021), https://www.virginiamercury.com/2021/06/28/governance-via-zoom-is-coming-to-an-end-in-virginia-should-it/.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] Va. Code Ann. § 2.2-3708.2 (2018).

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] Moomaw & Vogelsong, supra note 2; Va. Code Ann. § 2.2-3708.2 (2018).

[10] Moomaw & Vogelsong, supra note 2.

[11] Keeping an Eye on FOIA: The Debate Over Electronic Meetings, Virginia Press Association (Feb. 10, 2021), https://www.vpa.net/articles/keeping-an-eye-on-foia-the-debate-over-electronic-meetings/.

[12] Id.

[13] Allison Wrabel, As Local Government Meetings Moved Online, Public Participation Jumped, The Daily Progress (Mar. 16, 2020), https://dailyprogress.com/news/local/govt-and-politics/as-local-government-meetings-moved-online-public-participation-jumped/article_f7e98970-86b0-11eb-b1b9-c36c20bb6b3c.html.

[14] Id.

[15] Moomaw & Vogelsong, supra note 2.

[16] Id.

[17] Meetings Issues Subcommittee of the Virginia Freedom of Information Advisory Council, (June 24, 2021) (statement of Cullen Seltzer, Member, FOIA Council).

[18] Id.

[19] Virginia Freedom of Information Advisory Council, (July 19, 2021).